Please update your browser

Your current browser version is outdated. We recommend updating to the latest version for an improved and secure browsing experience.

Takemitsu and Akira Kurosawa

“I am enjoying swimming in the Ocean that has no West and no East.”

Tōru Takemitsu, postcard sent to Peter Serkin shortly before his deathThe Influence of Fumio Hayasaka

Conscripted into the Japanese army as a 14-year-old, Tōru Takemitsu was an autodidact who first encountered Western music through the phonograph and radio during and just after the Second World War.

Since Takemitsu never had the opportunity to formally study composition, his mentor Fumio Hayasaka (1914-1955) was a critical influence. Having already established a reputation as a concert composer in the late 1930s, Hayasaka attempted in the postwar period to rethink the relationship between dialectical, Western modes of music and continuous harmonic forms that might be compared to “Noh theater or picture scrolls.”

Significantly, Hayasaka was also one of the first classical composers in Japan to focus on film scores, and he remains most famous for his collaborations with Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998) on such films as Rashomon (1950), Ikiru (1952), and Seven Samurai (1954).

“I’ve never much cared for Kabuki, perhaps because I like Noh so much. I like it because it is the real heart, the core of all Japanese drama. Its degree of compassion is extreme, and it is full of symbols, full of subtlety…. In the Noh, style and story are one.”

Akira Kurosawa, Interview with Donald Richie

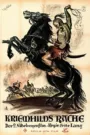

Throne of Blood

The influence of Noh theater is directly foregrounded at the beginning of Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957), as a Noh chorus chants about the mutability of human life and a castle slowly emerges out of an all-enveloping mist.

Noh and Wagner

Hayasaka passed away two years before Throne of Blood was made. When Kurosawa took his experiments with Noh even further and attempted a more full-scale integration of Noh tropes and Shakespearean tragedy in Ran (1985), he inevitably turned to Takemitsu. The result of the collaboration was a score that had the epic effect of Wagner's operas or the great Gustav Mahler symphonies (like the 2nd “Resurrection” Symphony, 1897), but with traditional Japanese instrumentation. Traditional Noh theater has a jo-ha-kyū rhythmic structure, with a slow build-up (jo), a period of intensification (ha), and then a rapid resolution (kyū). Zeami, the greatest aesthetic theorist of Noh, argued that this was connected to the fundamental flow of the universe and would enable the viewer to enter a state of heightened receptivity when he could experience yūgen, a profound, mysterious awareness of the beauty and tragedy of human destiny [1].

This sensibility is especially marked in the genuinely apocalyptic battle scene midway through the film, a scene with a montage rhythm that feels both abstract and inexorable. As Hidetora’s sanctuary is set ablaze and his armies are massacred, Kurosawa repeatedly cuts back to shots of clouds obscuring the light from the heavens, which gives the whole sequence a dark cosmic perspective. This technique, coupled with the elimination of diegetic sound and the consistent use of telephoto lenses throughout the battle, intensifies the tragic beauty of the sequence while also keeping the viewer at an aesthetic distance from the action by shifting the focus from the people below to the heavens above.

The King Lear-like Hidetora (Tatsuya Nakadai)’s inability to process the complete betrayal of his sons and the chaos that has ensued is suggested visually by the mask-like expression on his face. When Hidetora first appears on screen, he is hunting a boar like a man possessed and Kurosawa communicates the darkness of his character by painting his face to resemble an akujo mask. As the world collapses around him, he is transformed into the mad wanderer of the second half of King Lear, and his face suddenly begins to the very different shiwajo old man mask, with its strong wrinkles and empty eyes. The shift in consciousness is marked by a single gunshot sound, which marks the point where Takemitsu’s music shifts seamlessly into the diegetic sound of battle chaos. Appropriately, he labeled this part of the score “Hell’s Picture Scroll.”