Please update your browser

Your current browser version is outdated. We recommend updating to the latest version for an improved and secure browsing experience.

Adapting Wagner for the Screen

Wagner's Twentieth Century Legacies

In 1911, W. Stephen Bush, the influential critic for Moving Picture World who frequently expounded on the relationship between music and cinema had written that “Every man or woman in charge of [the] music of a moving picture theatre is, consciously or unconsciously, a disciple of Richard Wagner” [i]. Wagner’s mythopoeic works and their musical principles exerted an enormous influence on late 19th and early 20th century music, literature, and art (from the music of Claude Debussy to the paintings of Fernand Khnopff, the poems of Stéphane Mallarmé, and J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings).

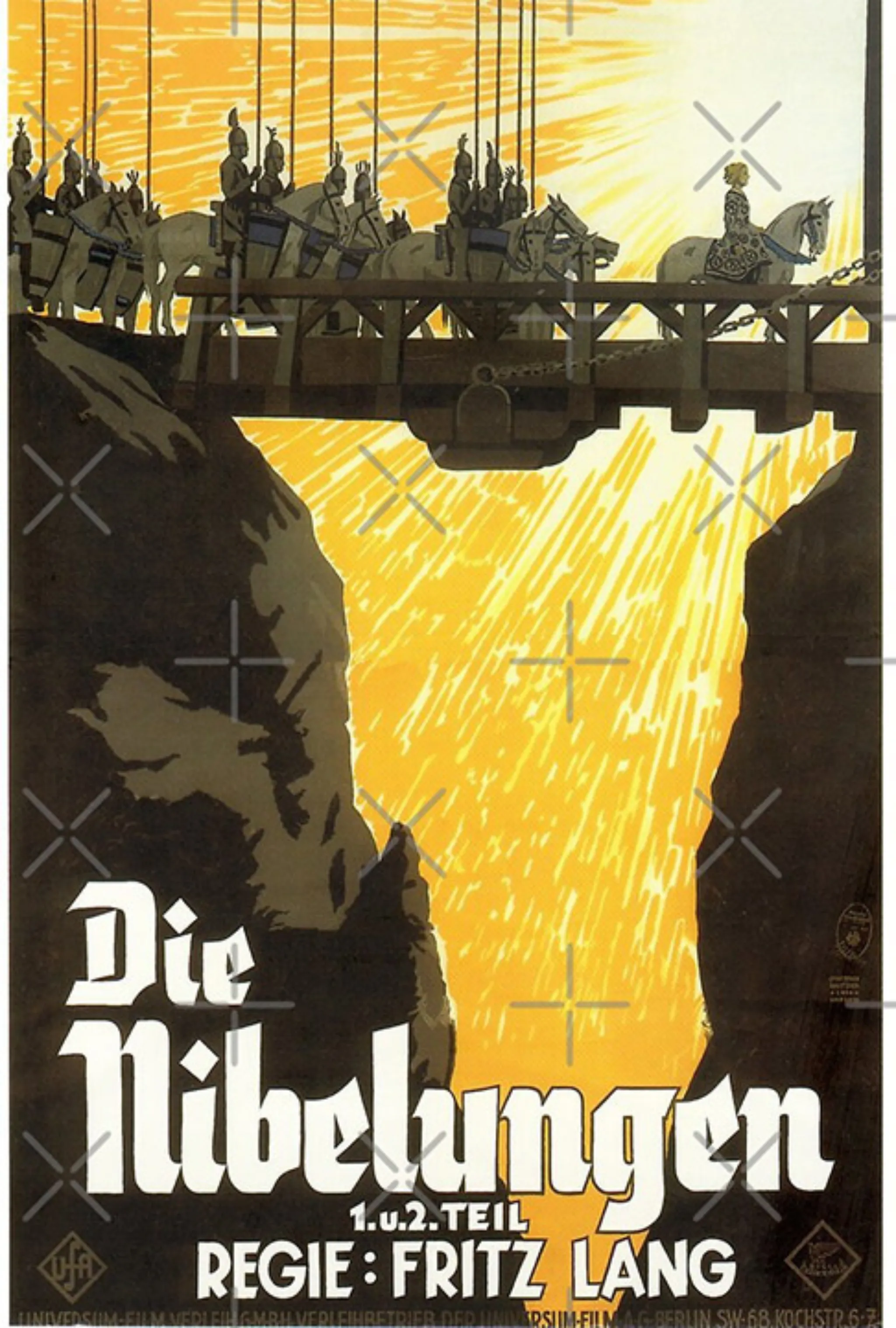

This was extended into cinema, both through epic adaptations like Fritz Lang’s Nibelungen films (1924) and the work of composers ranging from Max Steiner and Bernard Herrmann to Jerry Goldsmith and Hans Zimmer.

[i] W. Stephen Bush, “Giving Musical Expression to the Drama,” Moving Picture World, 12 August 1911

Die Walküre in Film

The use of actual extracts of Wagner music carries with it a whole host of associations, including the complex histories of the music (especially in the middle of the 20th century) and uses in previous films. In this way, music from Die Walküre, the second part of the “Ring cycle,” could be used to accompany political ascent in The Scarlett Empress (Josef von Sternberg, 1934), to suggest the permutations of l’amour fou (crazy love) in That Obscure Object of Desire (Luis Buñuel, 1977), or as a commentary on human violence in Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979).

The use of the piece by Buñuel is an implicit response to both the von Sternberg film and to the use of the Prelude to Tristan and Isolde (1859) in Buñuel’s own first film Un chien andalou (1929).

In Coppola’s film, by contrast, its use as accompaniment to a helicopter raid in Vietnam ironically echoes the iconic Ride of the Klan in D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), encouraging viewers to consider the degree to which the onscreen characters are trapped within an endless cycle of self-aggrandizing violence.

“I adored Wagner, whose music I used in several films, from Un Chien andalou to That Obscure Object of Desire. One of the greatest tragedies in my life is my deafness, for it's been over twenty years now since I've been able to hear notes. When I listen to music, it's as if the letters in a text were changing places with one another, rendering the words unintelligible and muddying the lines. I'd consider my old age redeemed if my hearing were to come back, for music would be the gentlest opiate, calming my fears as I move toward death. In any case, I suppose the only chance I have for that kind of miracle involves nothing short of a visit to Lourdes.”

Luis Buñuel, My Last Sigh: The Autobiography (1983)