Please update your browser

Your current browser version is outdated. We recommend updating to the latest version for an improved and secure browsing experience.

Labyrinths and Hedge Mazes

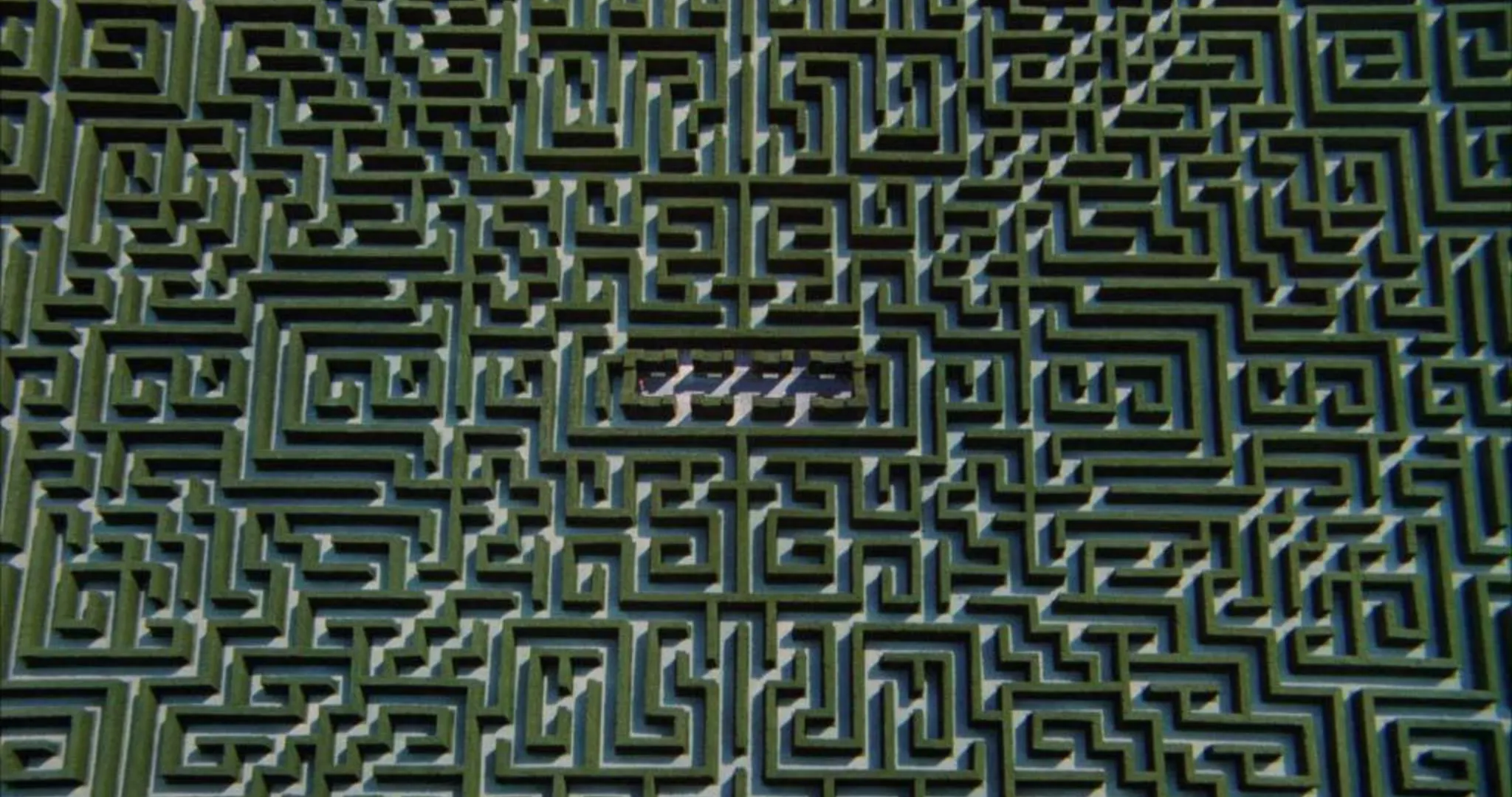

In The Shining (1980), Stanley Kubrick combines the three traditional associations of the hedge maze. The first is the ancient Greek labyrinth Minos commissioned Dedalus to build to permanently imprison the Minotaur in Crete. The labyrinth was considered impregnable and everyone sent there was doomed to death. Theseus was only able to defeat the half-man, half-beast and escape by using his wits, the art of memory, and the red thread Ariadne had given him to record his path.

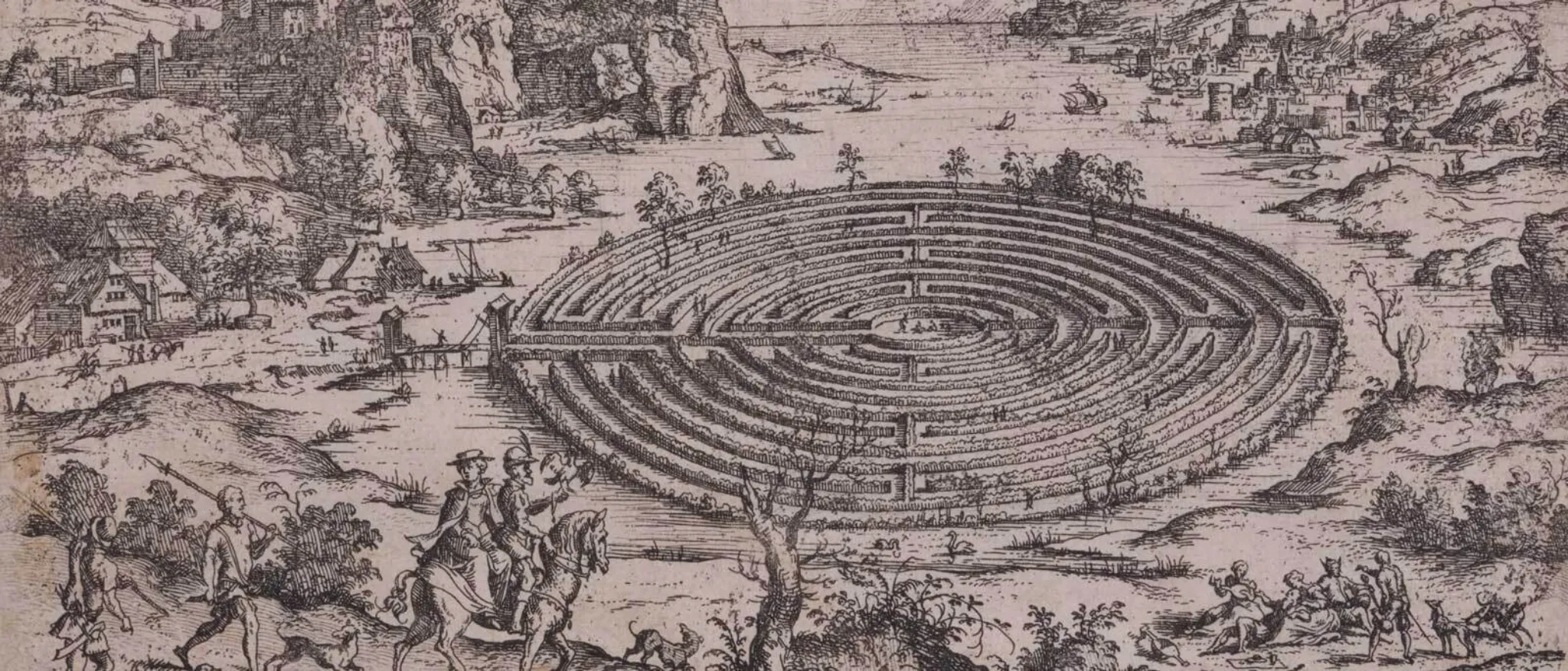

In the medieval world, labyrinths were re-envisioned as symbols of the wayward human journey of pilgrims yearning to reach the Celestial City. Journeying through a labyrinth was understood as a spiritual exercise and a way of training human experience and human memory to more fully align with the sacred coordinates of the universe.

In the late 17th century, hedge mazes, such as the one at Hampton Court in England and the now-lost one at the Palace of Versailles in France, were introduced as part of elaborate spatial displays, as demonstrations of human rationalization of the landscape, and as ways of connecting space and vision to secular power.

Kubrick builds upon all of these associations in the sequence below, associated by a long section from Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta (1936) by the pioneering modernist composer Béla Bartók (1881-1945).

Labyrinth of Chartres Cathedral (France)

The best preserved and most justly famous labyrinth of the High Middle Ages was constructed at Chartres in the early 13th century. Chartres is the greatest testament to the ambition and sophistication of Gothic architecture and every facet was designed to correspond to sacred measures outlined in texts by authors like St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430). St. Augustine wrote The City of God (426) as a response to the Sack of Rome in 410. In a similar fashion, the builders of Chartres Cathedral almost certainly intended the labyrinth inside to be the culmination of a pilgrimage journey, replacing the increasingly fraught pilgrimage to the city of Jerusalem during the Crusades. The placement of the labyrinth right near the entrance to the Cathedral has long made it a potent symbol of an interior quest.

The labyrinth stone now held at the Visitor's Center at Glendalough in County Wicklow, Ireland was discovered in 1908 on the pilgrimage road of St. Kevin, near the town of Hollywood. St. Kevin established Glendalough as one of the first monasteries in Ireland in the sixth century.