Please update your browser

Your current browser version is outdated. We recommend updating to the latest version for an improved and secure browsing experience.

Edward Steichen and Pictorialist Photography

Around the time of its first public presentations in 1895, the Lumière Brothers (Auguste and Louis, 1862-1954) are said to have called their invention, the cinématographe, an “invention without a future” because they viewed it as the culmination of a series of nineteenth century photographic experiments.

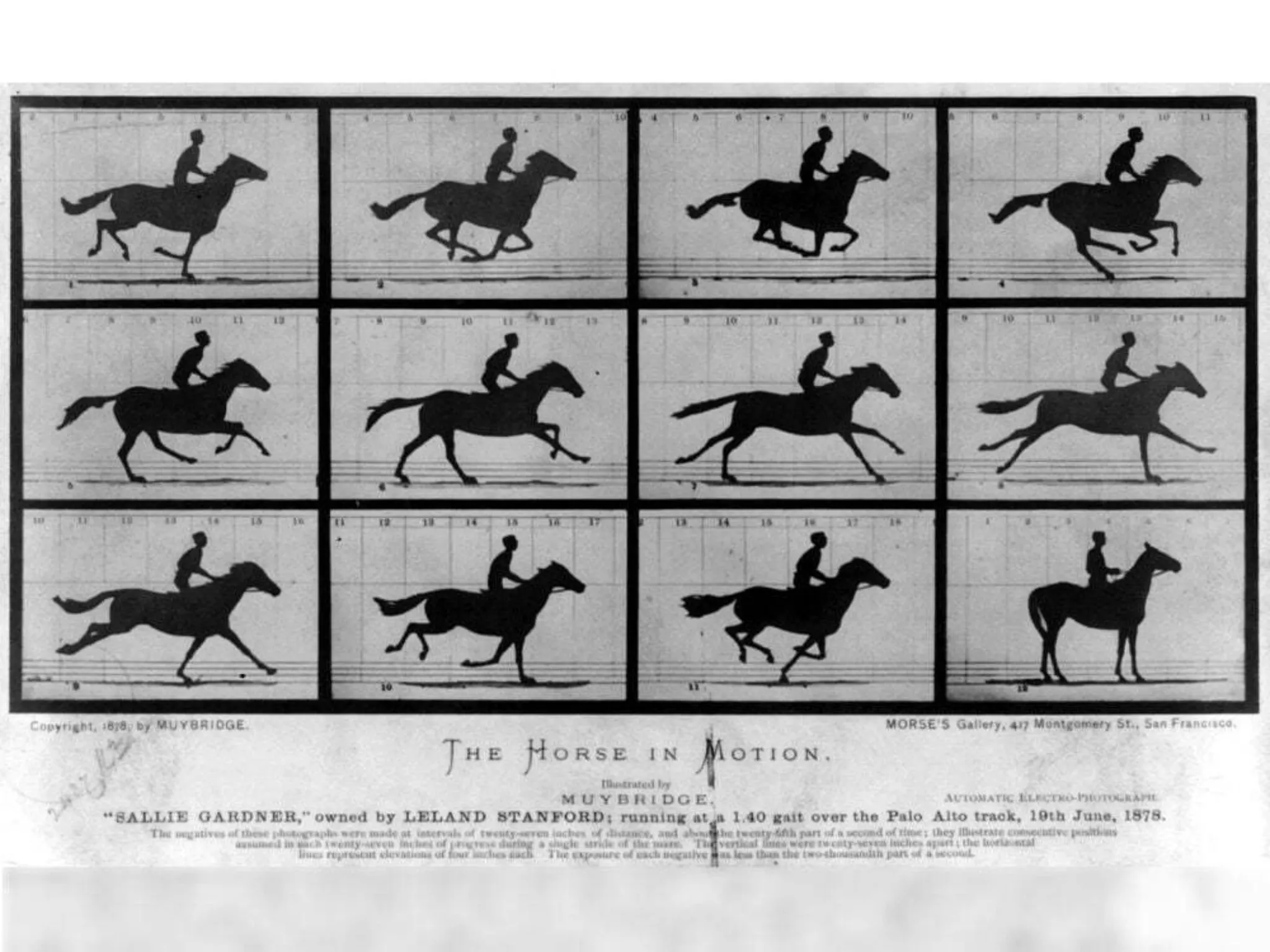

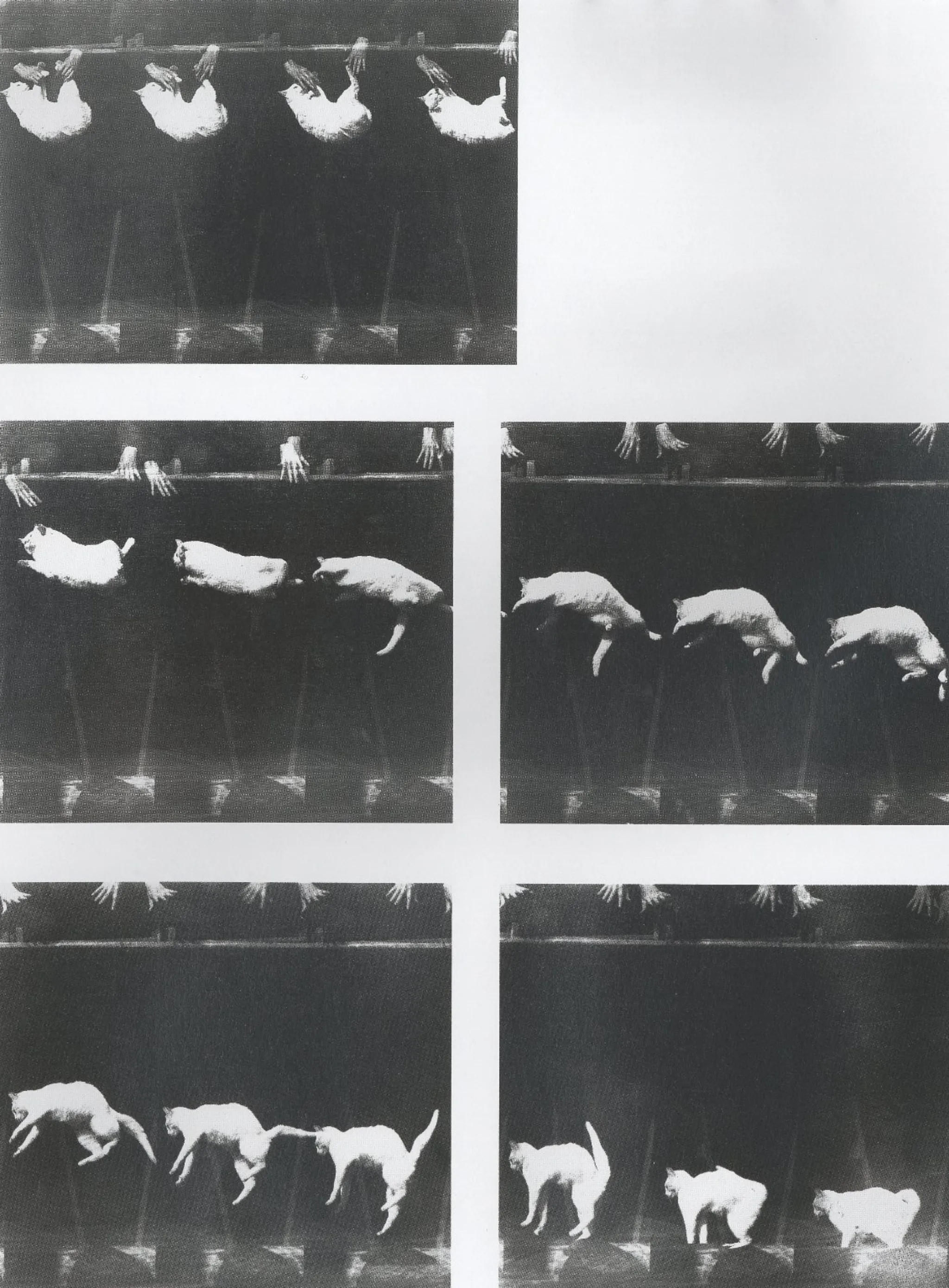

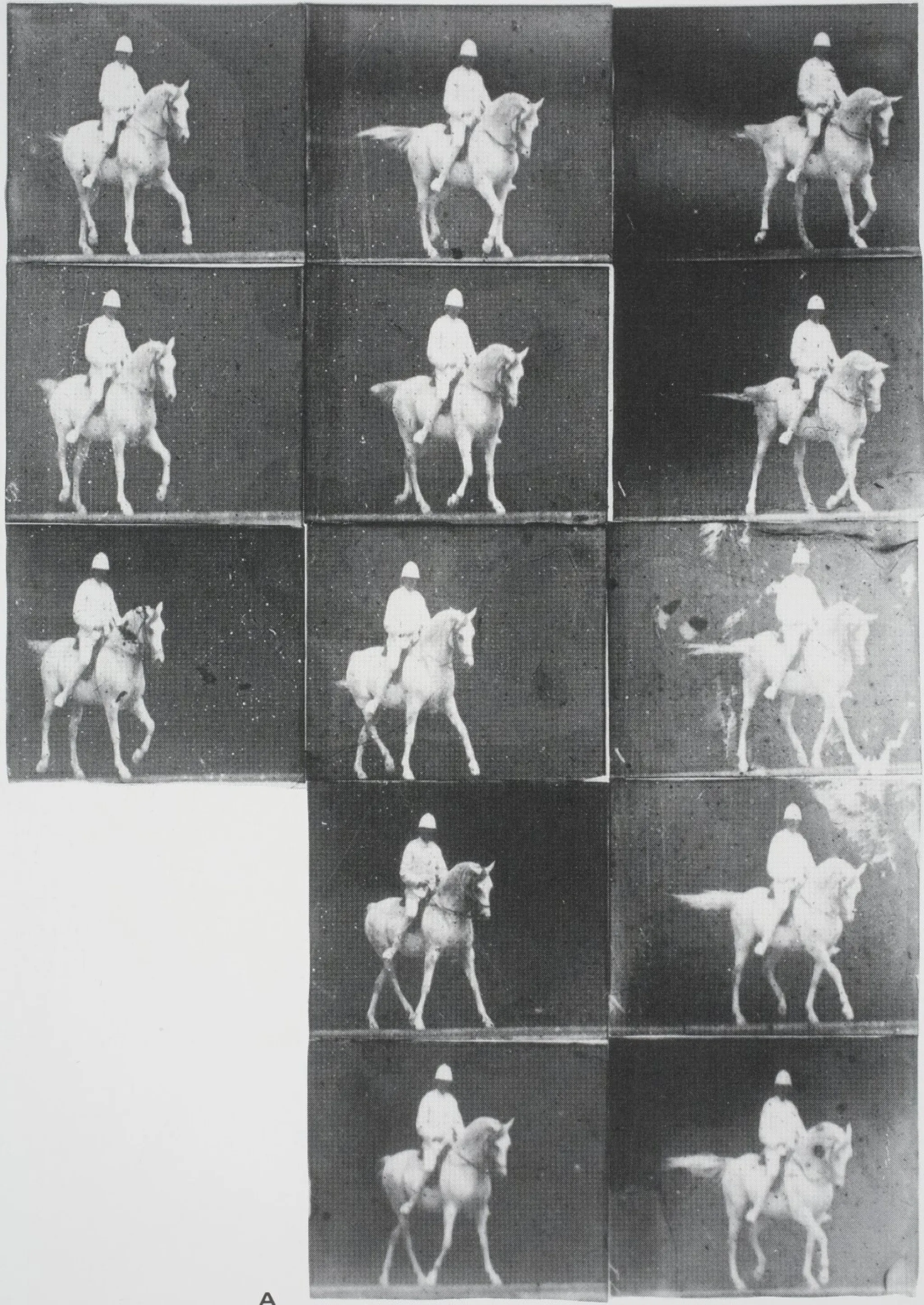

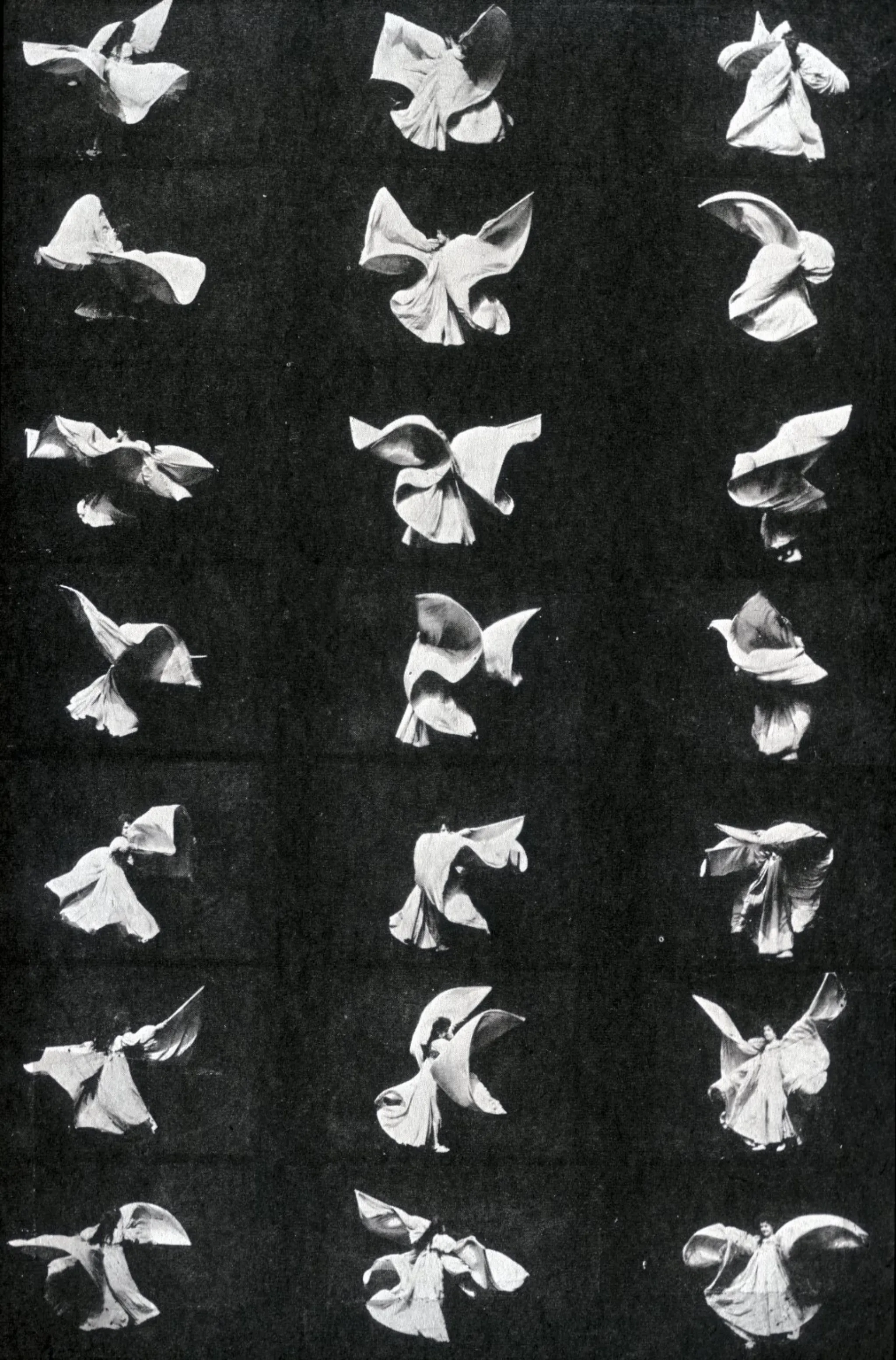

In 1872, English photographer Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) had been commissioned by railroad baron Leland Stanford to determine whether there was ever a moment when all of the legs of a running horse would be off the ground. The system of sequential photography Muybridge developed and demonstrated several years later helped to clarify the stakes for what would become motion pictures by showing that motion could be broken down into a series of progressive phases.

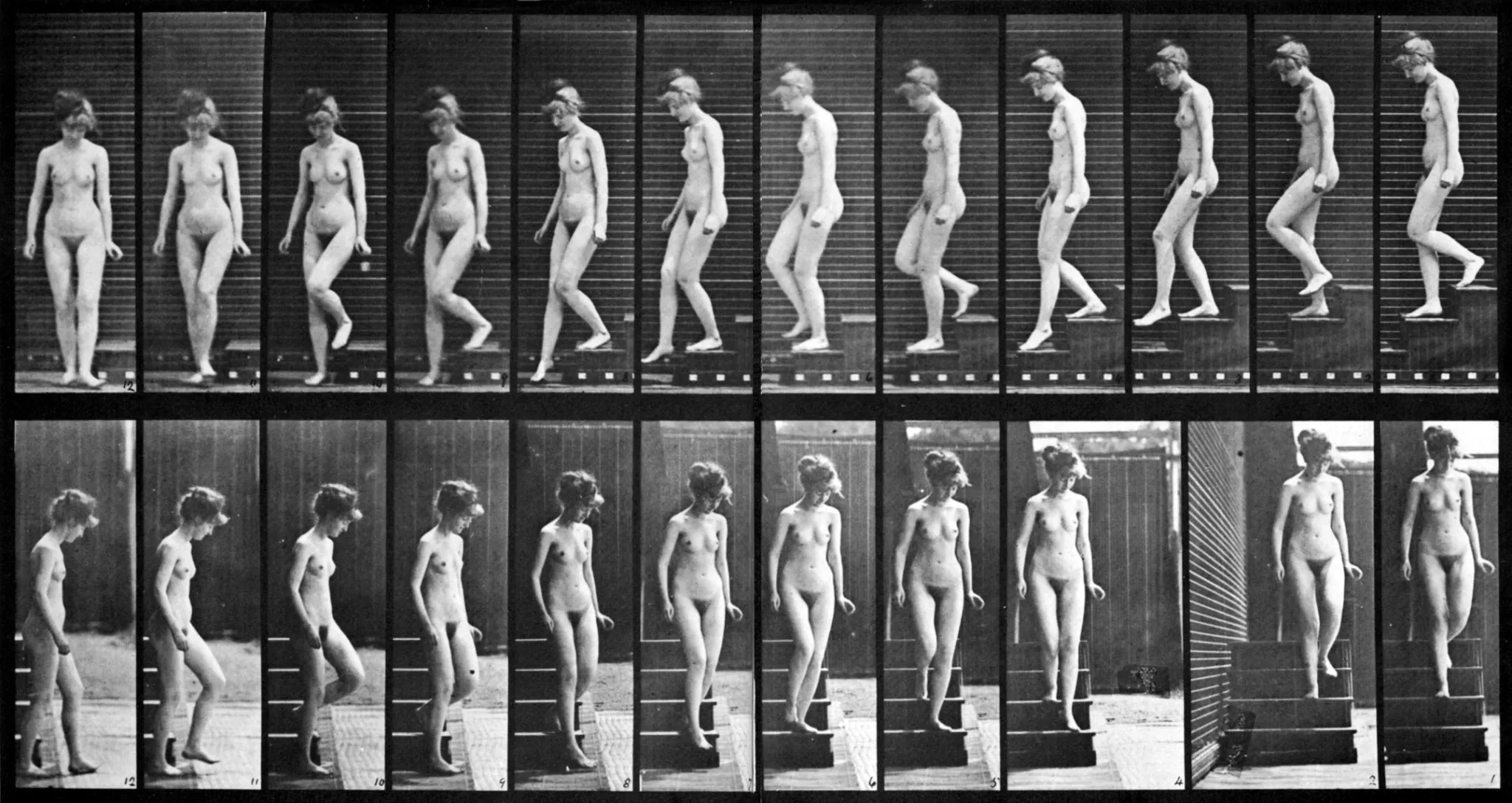

Woman Walking Down Stairs (Eadweard Muybridge, 1887)

What remained was for Muybridge and other inventors such as Étienne Jules-Marey (1830-1904), Thomas Edison (1847-1931), and the Lumières to reverse the process and to present a series of successive still images with sufficient rapidity that the viewer would accept the illusion of motion:

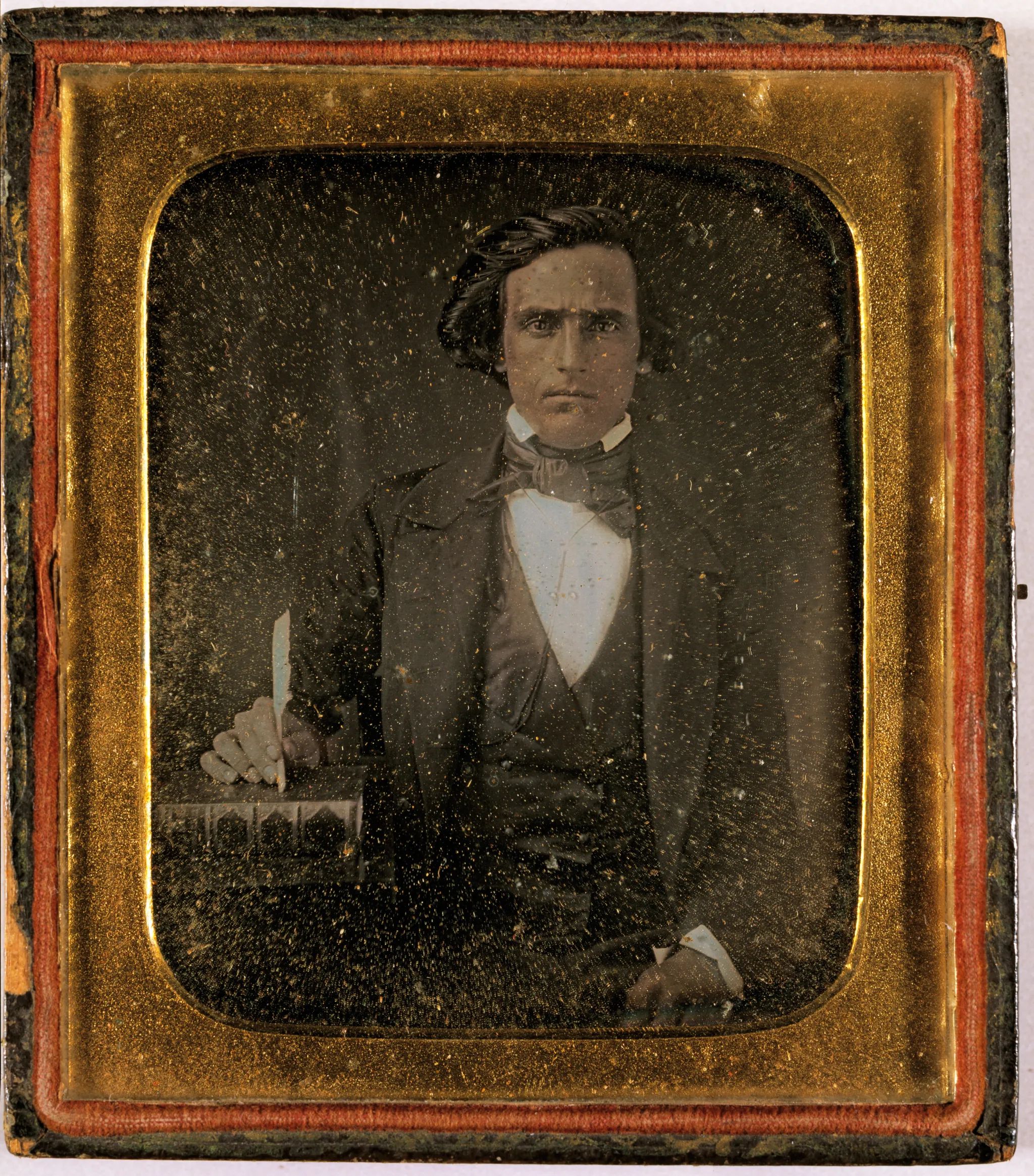

Daguerreotypes

Photography itself had began several decades earlier with two models – one French, the other English – that both highlighted the fundamental tension between presence and absence. First came the daguerreotype, a singular imprint of light captured in a small, generally framed image eponymously named after inventor Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851) and publicly presented in 1839.

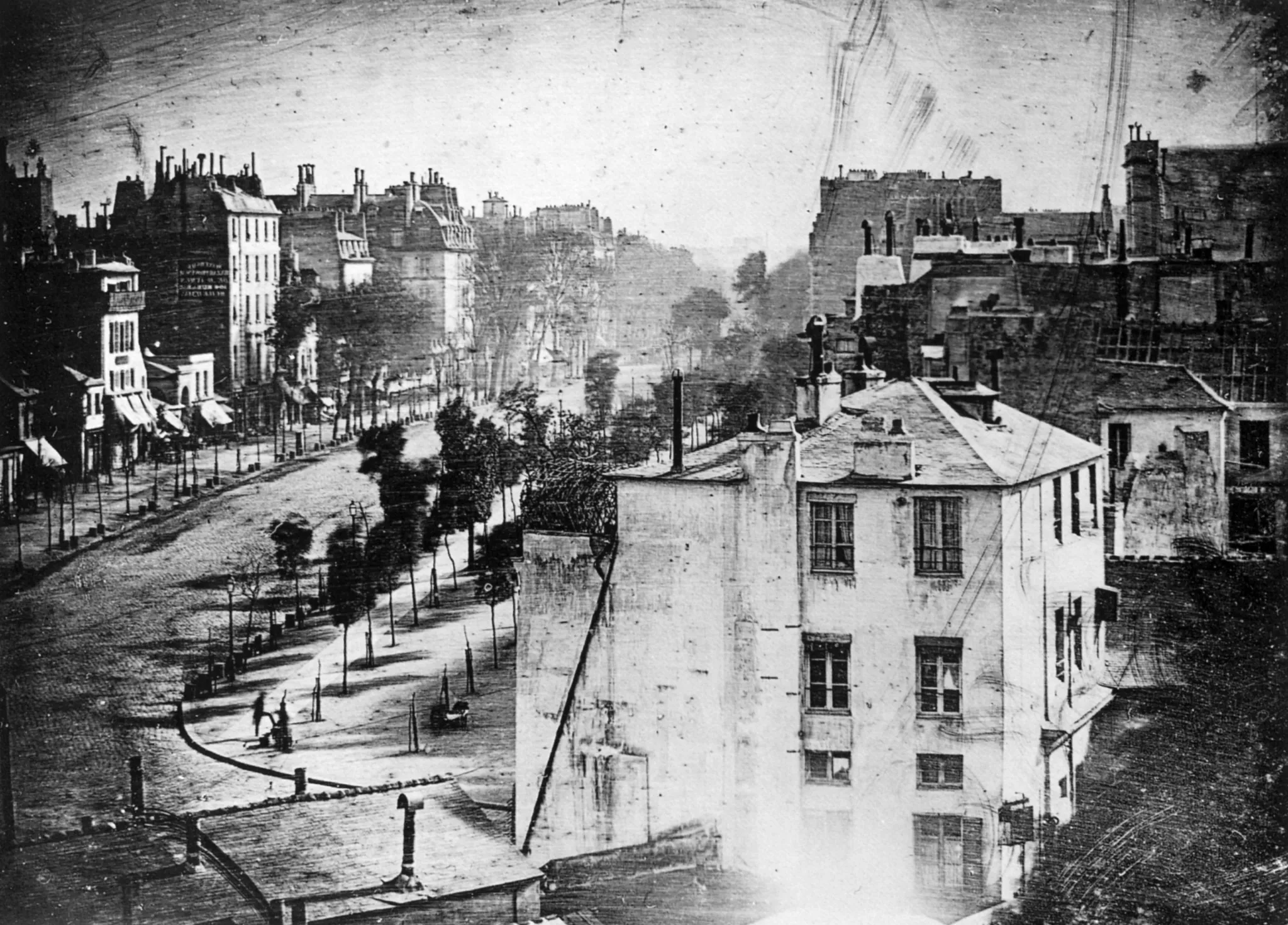

Presence and Absence

The several-minute-long exposure times of the time could result in technical problems and haunting images like this image of the Boulevard du Temple in Paris in 1838. The center of the theater district and one of Paris’s busiest thoroughfares is rendered virtually people-less by the several-minute-long exposure times of the period. Only the ghostly presence of a person standing mostly still having his shoes shined testify to the bustling life of the city that is otherwise invisible in this image.

William Henry Fox Talbot's Paper Prints

English inventor William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) developed a different system based on paper prints, which debuted in 1841. Fox Talbot’s system introduced many of the aspects that would become fundamental parts of both photographic and cinematographic processes, especially the creation of positive prints from a negative, which made mass reproducibility possible. Fox Talbot also produced the first photographic book, The Pencil of Nature, in 1844.

Several images explicitly attempt to imbue the new mechanical instrument with the aura of art, especially Plate 6, The Open Door. The treatment of lightness and darkness is rich and distinctly photographic. As Fox Talbot himself acknowledged in the commentary, however, the poetic use of transitional spaces, and of objects such as the broom that directly parallels the shadow that diagonally divides the centrally positioned doorway, is strongly evocative of the Dutch genre painting associated with figures like Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) and Pieter de Hooch (1629-1684).

“We have sufficient authority in the Dutch school of art, for taking as subjects of representation scenes of daily and familiar occurrence. A painter's eye will often be arrested where ordinary people see nothing remarkable.”

William Henry Fox Talbot, The Pencil of Nature

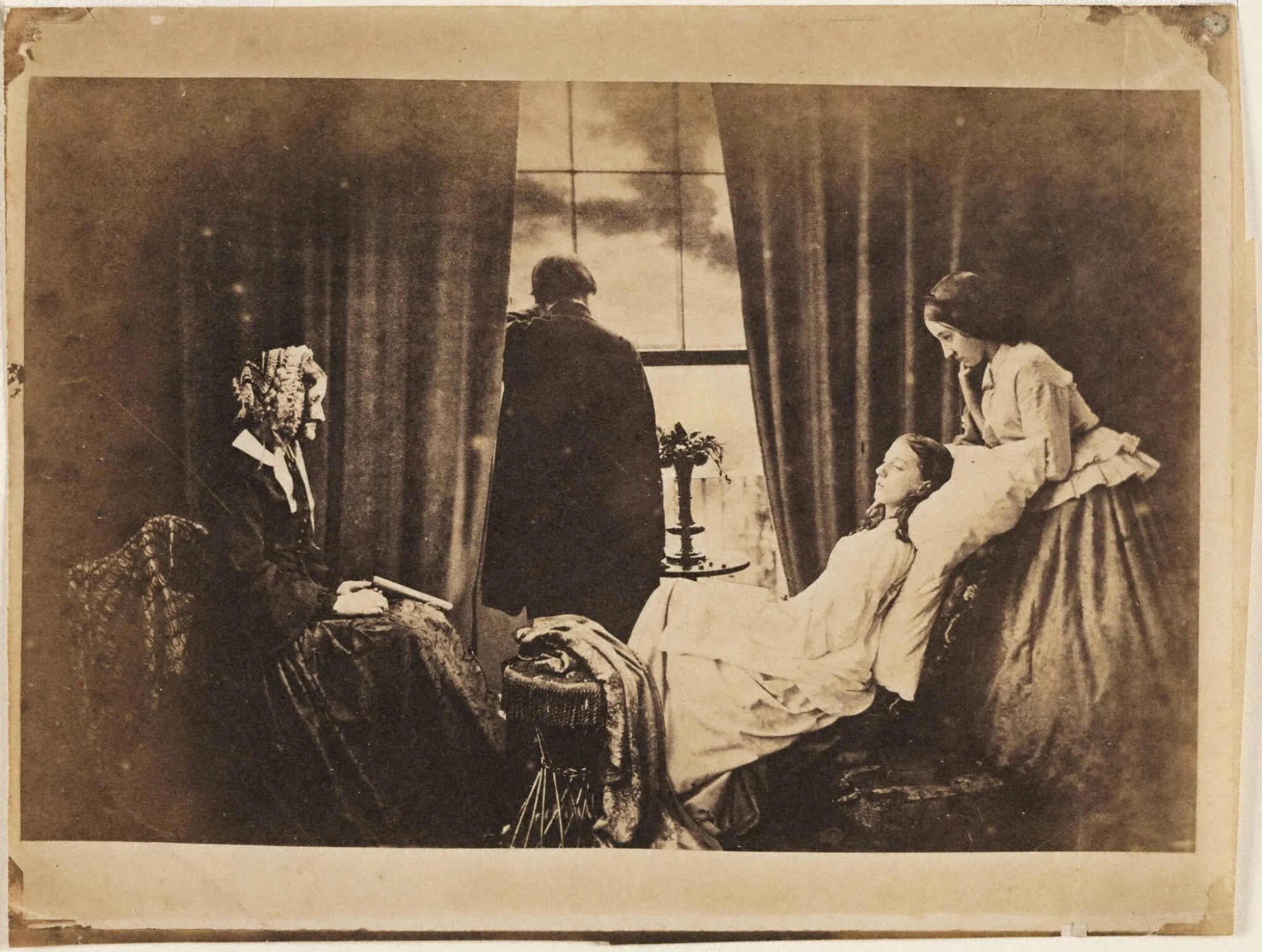

Henry Peach Robinson and the Picturesque

Later nineteenth century photographers such as Henry Peach Robinson went even further in attempting to construct "picturesque" composite photographs that would have a painterly effect.

Steichen's Symbolist Photography

Edward Steichen (1879-1973) is emblematic of the transition between nineteenth and twentieth century approaches. Born in Luxembourg, Steichen was heavily influenced by late nineteenth century Symbolist aesthetics, with its predilections for enigma, synthetic forms, and the Gesamtkunstwerks of Richard Wagner. Steichen used the German Symbolist publication Pan as a model for the design of the pioneering photographic journal Camera Work, which was published by Alfred Stieglitz from 1903 to 1917.

In The Flatiron, Steichen introduced paint pigments in a suspended chemical solution to transform an image of a quintessential work of modern architecture – the recently constructed headquarters of the Fuller construction company in New York – into an exploration of color and mood that invites comparison with the contemporaneous work of painters like Jame McNeill Whistler while also remaining uniquely photographic.