Please update your browser

Your current browser version is outdated. We recommend updating to the latest version for an improved and secure browsing experience.

- F. W. Murnau

- Germany

- Silent Film

- Horror

- Max Schreck

- Gustav von Wangenheim

- Greta Schroeder

- Albin Grau

- Prana Film GmbH

- Fritz Arno Wagner

- Henrik Galeen

- Bram Stoker (uncredited adaptation of Dracula)

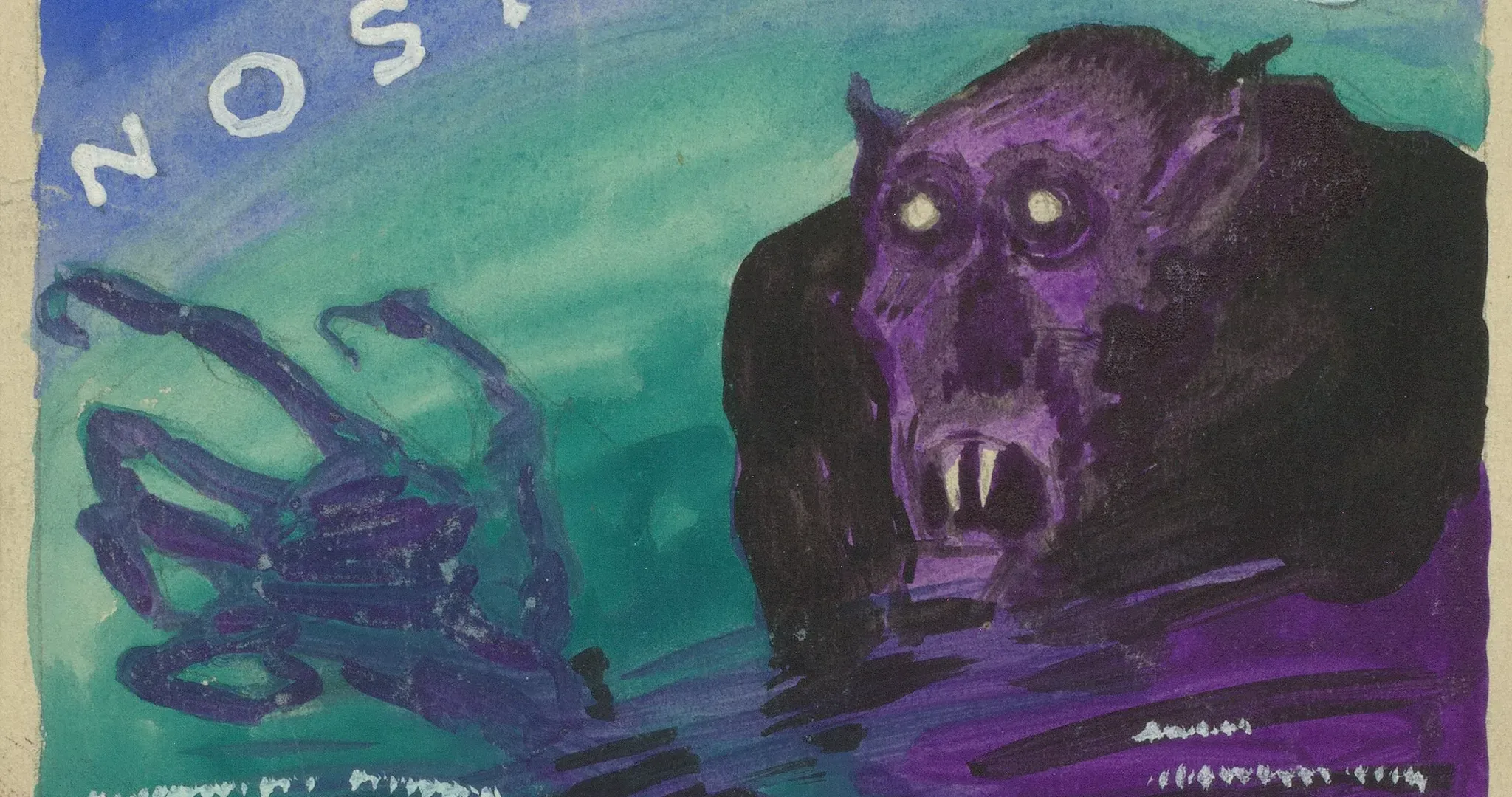

An unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897) and a small, independent production, Nosferatu's survival and endurance is as surprising as the film itself. Stoker's novel, written at the very moment of cinema's emergence, is the most well-known literary distillation of legends surrounding vampires in the Transylvanian region of Central Europe (in what is now Romania), which allegedly go back to the 11th century.

Producer and production designer Albin Grau said that the real impetus for the adaptation was a chance meeting with someone claiming direct knowledge of vampires during the First World War. Grau had a pronounced interest in the occult and named his production company Prana Films after a Sanskrit word for "life force."

Bram Stoker's descendants were unpersuaded by Grau's story and successfully sued. In 1925, a judge ordered all prints destroyed, and yet the film has continued to circulate in many different forms for decades. It has become so strongly associated with the art of the Weimar period that, for later directors like Werner Herzog and Jean-Luc Godard, responding to it is a way of coming to terms with both Germany's complicated twentieth-century history and with the history of cinema itself.

Inventing Murnau

F. W. Murnau (1882-1931) was born Friedrich Wilhelm Plumpe in Bielefeld, North Rhine-Westphalia. He adopted the name "Murnau" in honor of the artists' colony south of Munich that was home to Wasily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, and Gabriele Münter during the short-lived, but influential "Blue Rider" Expressionist movement (1911-1914). Murnau's passion for Expressionist art is unsurprising given the geometric proclivities demonstrated by his later films, but he was equally interested in more traditionally representational forms of painting, especially the Old Masters and the Romantics. He spent much of his youth in Kassel (which has one of the most well-known Old Master collections in Germany) and studied art history at the University of Heidelberg for several years. Murnau wore a lab coat on set and was referred to as "Herr Doktor," but his studies were never completed thanks to a sojourn with Max Reinhardt and the Deutsches Theater and then the outbreak of the First World War.

After service in the Air Force, Murnau turned to cinema, forming an independent company with Conrad Veidt in 1919. Many of Murnau's early works are lost, which makes the survival of Nosferatu all the more remarkable.

Murnau's art historical background is not only evident in the direct reworking of several 19th century Romantic paintings made in the Northern German regions in which the film was shot. It is also manifest in the constant tension between assertive, jutting triangles (like ship masts and coffins) and the curved archways that mark liminal passage into mysterious domains, like Count Orlok's castle, that are explicitly associated with death. The turn to Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) is in no way superficial, and is particularly associated with the figure of Ellen. Her interior life and privileged vision is repeatedly stressed, as in many Friedrich paintings, by her frequent placement next to doorways and windows.

In the sequence below, the viewer's perspective is overtly aligned with that of Ellen, as she glances out at a row of coffins passing through the center of town. Nosferatu takes place in 1838, but the haunting image inevitably evokes the traumatic shocks and mass slaughter of the First World War.

A Baltic Film

Caspar David Friedrich was born in Greifswald, Pomerania, originally as a subject of the Swedish crown. Many of his paintings depict the Baltic coast areas of northern Germany, particularly the areas near the island of Rügen. This area was of particular importance from the 12th to the 15th centuries due to the Hanseatic League, a defensive and trading confederation of important port cities.

Nosferatu takes place in an imaginary city called Wisborg located near the Black Sea, but the architecture is distinctly Hanseatic and the landscapes are Baltic. Murnau shot primarily in the former Hanseatic capital, the Free City of Lübeck, and in Wismar. He transformed buildings associated with mercantile exchange - like the Salt Storehouses (first built in 1579) in Lübeck and the Water Gate in Wismar - into the ghostly, semi-ruined domains of the vampire.

The use of location shooting was very atypical for Weimar cinema, but Murnau connected it to the much more characteristic emphasis on lighting and on the transitions between day and night. This is undoubtedly one of the reasons why Nosferatu seems both of its period and eerily timeless.

Spiritual Journeys and Cinematic Passages

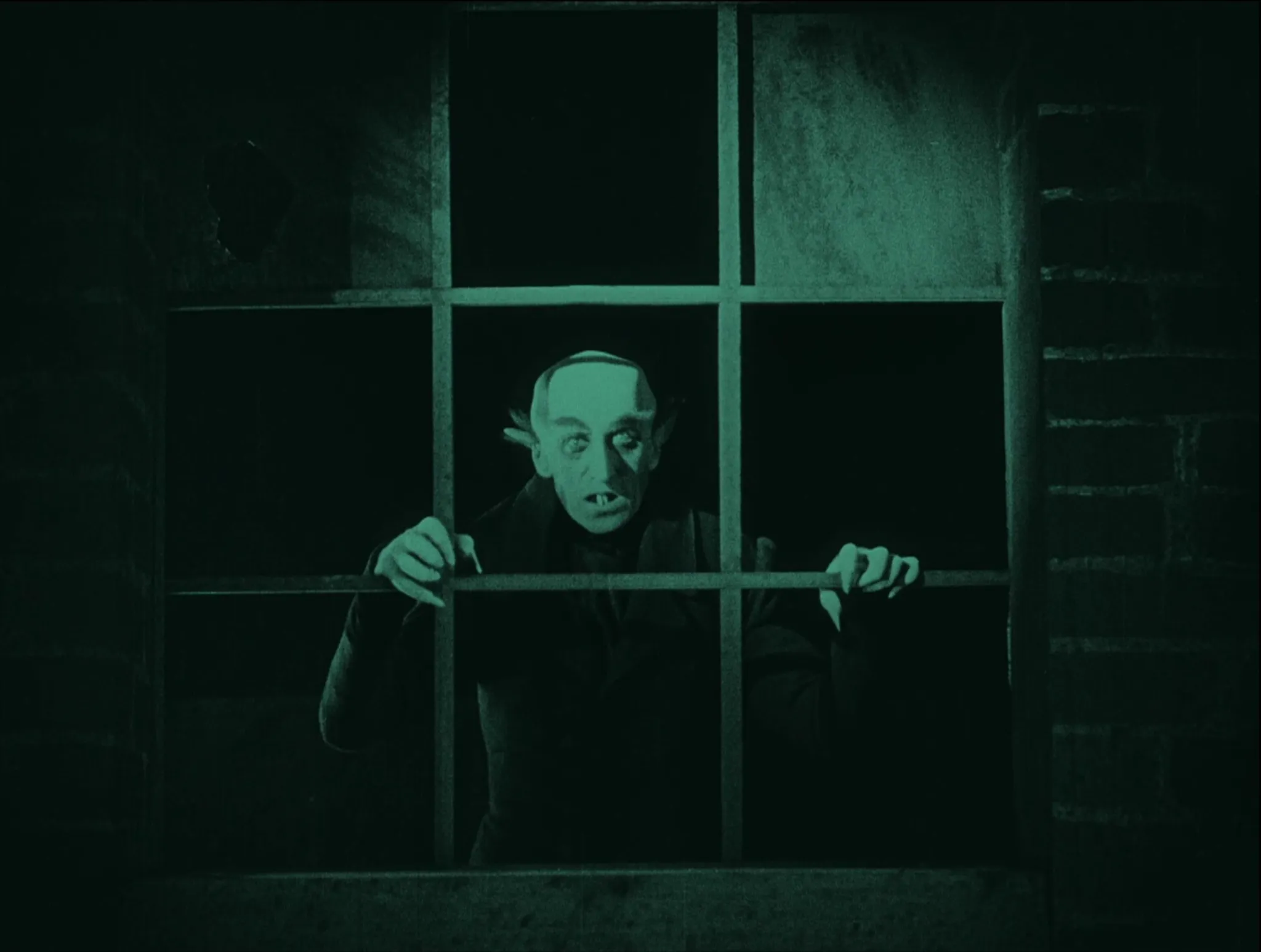

From his first appearance on a mountain path, Orlok's unusual status and capabilities are demonstrated through cinematic devices. There is a switch from positive to negative film in the journey to his castle, he is later superimposed atop his coffin, and stop motion is associated with his movements on several occasion. Most importantly, he is specifically linked - especially once he reaches the Salt Storehouses - with openings that strongly resemble film frames.

When Ellen tries to describe "what she sees every evening" to Thomas, we see Orlok between these frames. Ellen was herself earlier associated with equally frame-like window panes (see below). Her uncanny connection with the vampire and everything he represents is elsewhere linked with Caligari-like hypnosis and especially with a reworking of parallel editing. Where earlier filmmakers like D. W. Griffith and contemporaries like Fritz Lang used cross-cutting to poetically link spaces and narrative events, Murnau uses it in Nosferatu to suggest a more mysterious connection between Ellen and her seeming opposite (the vampire and his death-like domain). In the first example below, she is able to intervene to protect her beloved, while the apocalyptic associations of the second extended exercise in parallel editing sets the stage for the sacrifice and transformation that ends the film. In every case, Murnau connects the psychic exchange linking the characters to natural elements, and especially to the implacable movement of the sea.

Appropriately, the vampire, having lost his supernatural control of the mechanisms of cinema after his sexualized encounter with Ellen, is destroyed by light.

Crossing the Bridge

André Breton, the key figure of the Surrealist movement [1], wrote ebulliently in the late 1920s about one of the intertitles that accompanies the first meeting of Thomas and Orlok in Nosferatu: "When he crossed the bridge, the phantoms came out to meet him." Two very different filmmakers, both influenced in different ways by Breton, returned to this imagery in their attempts to grapple with the post-Weimar era histories of German Romanticism and of German culture.

Werner Herzog remade Murnau's entire film in 1979, a few years after his mythic journey on foot from Munich to Paris to meet a dying Lotte Eisner [2]. Eisner had written a pioneering book on the stylistic roots of German Expressionism, The Haunted Screen (1954) [3], and had helped to establish the Cinémathèque française. Going to meet Eisner was, for Herzog, a way of putting his own West German films in direct dialogue with the silent German cinema and with the exile that, for many, followed. Herzog boldly reinvigorates the original Nosferatu's close ties with German Romanticism by using the opening chords of Richard Wagner's Ring Cycle to accompany the sepulchral encounter with the vampire.

Jean-Luc Godard made Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (1991) on the eve of German reunification, as a pendant to his then-ongoing Histoire(s) du cinéma project (1988-1998). In this extract, the fictional journey of abandoned Cold War spy Lemmy Caution across the "Inner Border" separating East and West Germany is part of a montage that also includes the Nosferatu intertitle celebrated by Breton, allusions to Oswald Spengler's The Decline of the West (1918), and passages from Beethoven's Seventh Symphony (1812).

The Cinematic Uncanny

The most extraordinary moment in Nosferatu occurs during the scene below, when the vampire carries his own coffin (and all the death and disease that comes with it) into the city. Murnau beautifully juxtaposes the protruding, angular form of the coffin with the echoing curves of both the vampire's head and the archway of the Water Gate above. Just after Nosferatu passes through the gate, a bird flies under the tower in the opposite direction.

This single shot encapsulates what is most powerful and profound in Nosferatu, the miraculous fusion of elegantly staged compositions and movements with the completely spontaneous vitality that cinema alone can capture.

Restoration Credits

NOSFERATU - Eine Symphonie des Grauens

Germany 1921

Director Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau

Script Henrik Galeen

Based on Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’

Costume & set design Albin Grau

Photography Fritz Arno Wagner

Production Prana Film GmbH

Cast

Max Schreck Count Orlok

Gustav von Wangenheim Hutter

Greta Schroeder Ellen, his wife

G. H. Schnell Harding, a shipowner

Ruth Landshoff Ruth, his sister

Gustav Botz Professor Sievers, the town doctor

Alexander Granach Knock, a house broker

John Gottowt Professor Bulwer, a Paracelsian

Max Nemetz A captain

Wolfgang Heinz 1st sailor

Albert Venohr 2nd sailor

Restoration (2006) Luciano Berriatúa

on behalf of Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung

Material Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv

Cinémathèque Française

Laboratory L'Immagine Ritrovata

Titles and intertitles trickWilk GmbH

Digitization (2013) Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung

Digital image editing Arri Film & TV Services GmbH

and mastering

Score (2022) Olav Lervik (p.p. ZDF / ARTE)

Publisher 2eleven edition musiQ

Recording Ensemble der/gelbe/klang

Tobias Kaiser Flute, piccolo, alto flute

Claire Sirjacobs Oboe

Oliver Klenk Clarinet, bass clarinet

Inès Pyziak Bassoon, contrabassoon

Ona Ramos Tintó Horn

Philipp Lüdecke Trumpet

Adrián Albaladejo Diaz Trombone, bass trombone

Manuel Alcaraz Clemente Percussion

Patrick Stapleton Percussion

Marco Riccelli Keyboard

Nina Takai Violin

Anna Sophie Dauenhauer Violin

Alba González i Becerra Viola

Katerina Giannitsioti Violoncello

Benedict Ziervogel Contrabass

Der/gelbe/klang is supported by the Cultural Department of the City of Munich and the District of Upper Bavaria.

Musical director Armando Merino

Sound engineer Hartmut Bauer

Thomas Schmölz

The music recordings at the Festspielhaus

Erl/Tyrol from January 22 to 26, 2022 were made possible with the kind support

of the Tiroler Festspiele Erl Betriebsgesellschaft .m.b.H.

Music producer Thomas Schmölz

2eleven music film

Editor Nina Goslar

A co-production of

Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung, ZDF, 2eleven in collaboration with ARTE.

© 2006 / 2022