Please update your browser

Your current browser version is outdated. We recommend updating to the latest version for an improved and secure browsing experience.

- Fritz Lang

- Germany

- Thriller

- Early Sound

- Edvard Grieg

- Peter Lorre

- Otto Wernicke

- Gustaf Gründgens

- Paul Falkenberg

- Seymour Nebenzal

- Fritz Arno Wagner

- Fritz Lang

- Thea von Harbou

M was Fritz Lang's first sound film and the first of two films he made for Nero-Film AG, an independent production company under the leadership of producer Seymour Nebenzal. From 1928 to 1933, Nebenzal supported innovative, artistically experimental, and socially conscious films, envisioning his studio as a safe haven from Nazi control of the film industry. The much larger UFA (which financed superproductions such as Lang's Die Nibelungen) had been purchased in 1927 by media magnate Alfred Hugenberg, who became Reich Minister of Economics under Adolf Hitler. Lang and Nebenzal's second film, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) was the last of the great Weimar films and the first to suffer under Nazi censorship (Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels hated the film and it was not released in Germany until 1951). Both Nebenzal and Lang went into exile and the Nero-Film heritage is now maintained by Praesens-Film AG in Switzerland.

M is, among other things, an incisive portrait of the conditions and atmosphere shaping this period of massive transition. It is presented here in an extraordinary restoration supervised by Martin Koerber and the Deutsche Kinemathek (these efforts will be explored in a future program).

A True Sound Film

The period in which the international film industry transitioned to sound (ca. 1927-1933) was marked by anxiety as well as excitement. Sound recording technology created many new challenges during both shooting and editing, and many directors worried that the freedom of the camera epitomized by German Expressionist films would be restrained or even completely inhibited by the exigencies of sound filmmaking. The comparatively static, stage-influenced style of many early "Talkies" further reinforced these concerns. With M, Lang created one of the first films in which sound is an active shaping presence affecting every aspect of the film's design. This did not mean, however, that sound is used continuously from start to finish (as it is in most contemporary films).

There are many passages of silence and even important sections, especially those with highly mobile cameras, that are shot and structured in the manner of the silent films Lang was used to making. Lang instead focused on certain recurring sound elements (the sound of a ball, children's voices, doors opening and closing) that would appear, shift, and return alongside complementary visual motifs (hands, mirrors and windows, maps) in the manner of Richard Wagner's leitmotifs.

The most vivid and recognizable of these is Hans Beckert's whistled rendition of Edvard Grieg's "In the Hall of the Mountain King" (Opus 23, 1875 as incidental music for the Henrik Ibsen play Peer Gynt and Opus 46, 1888, for the more well-known version at the end of the first Peer Gynt Suite). From the opening scene on, each appearance signals the arrival of Hans Beckert and the attendant danger to children and it is this leitmotif that enables the blind balloon-seller to recognize him. The complex structure of Lang's carefully calibrated use of sound is demonstrated by the clips and images below.

In the Hall of the Mountain King

Peer Gynt Suite (Edard Gieg, Opus 46, 1888, conducted by Rafael Kubelik, 1964)

The Opening Sequence of M

M begins in darkness and the viewer hears a children's game being played before seeing anything. In this way, Lang, always meticulously precise and clear, is already highlighting essential motifs and "teaching" viewers how to understand an artistically designed sound film. The continuous sound is matched by the movement of the camera to make spatial relationships (between the courtyard below and the homes inside the building) clear and also to set the stage for the cross-cutting between Elsie Beckmann's return from school and the mother's anticipation of her arrival. These spaces are not connected, so Lang relies upon a series of associations (such as matching the sound of the clock with the sound of the school bell).

Elsie Beckmann's near accident in the road anticipates the much greater danger she will face when she encounters Hans Beckert. The sounds of the car horns is subtly connected to the quieter and more rhythmic sound of the ball hitting the pavement and then the "Who is the Murderer?" sign. Having clearly established the overall situation and dynamics, Lang is now able to use absence and expectation for dramatic effect, as he cross-cuts between Elsie's journey with Beckert on the streets and the mother's increasing concern at home. Just after the first appearance of the "In the Hall of the Mountain King" whistling, a variation on the car horn sound appears as the ringing of a doorbell at home.

Lang concludes the sequence by linking the mother's cries of "Elsie" to a series of synechdocal ellipses - an empty table setting, the rolling ball, the balloon caught in wires - that vividly convey the horror of what has taken place while also suggesting vigorous new possibilities for sound cinema.

Visual and Sound Motifs

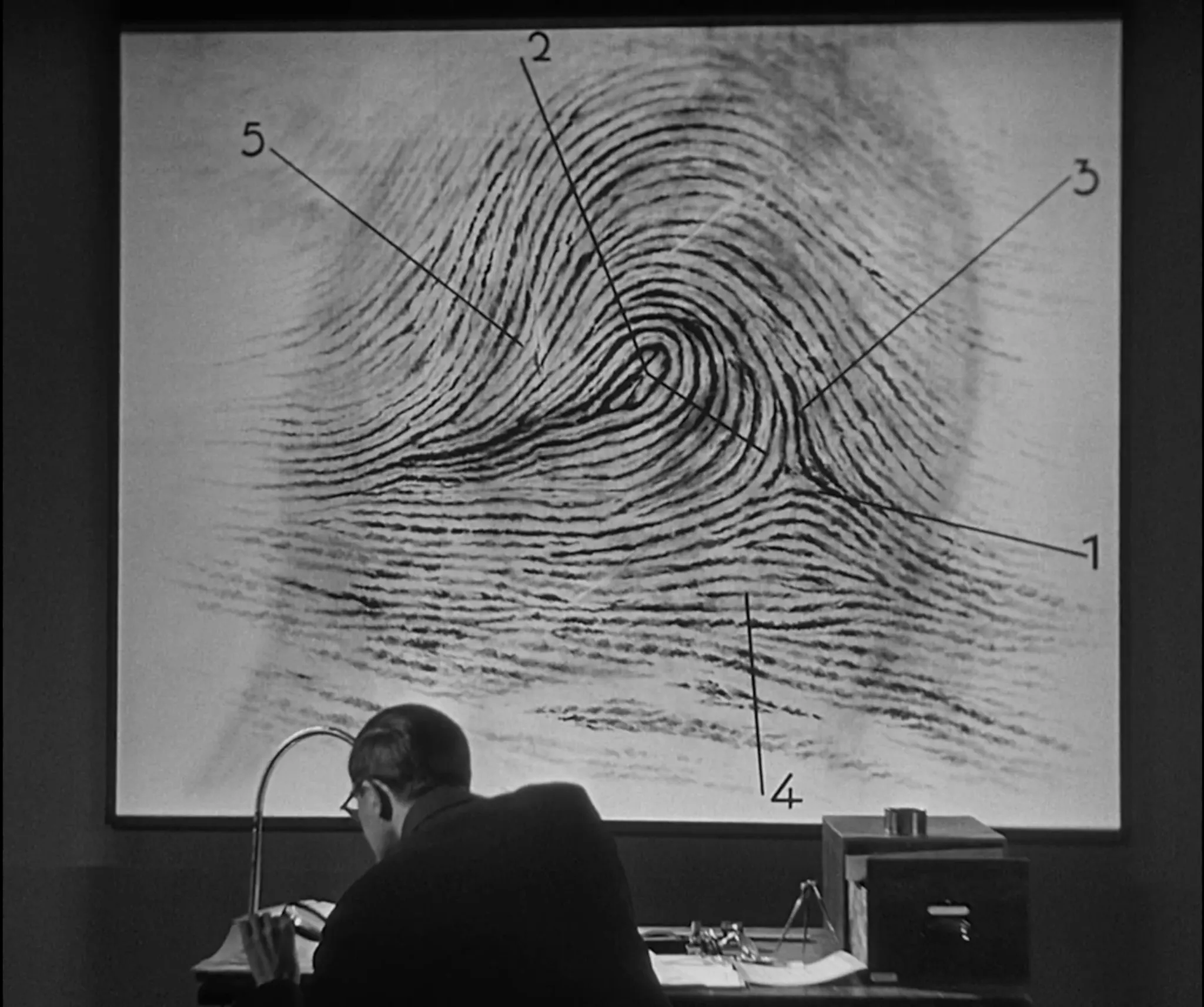

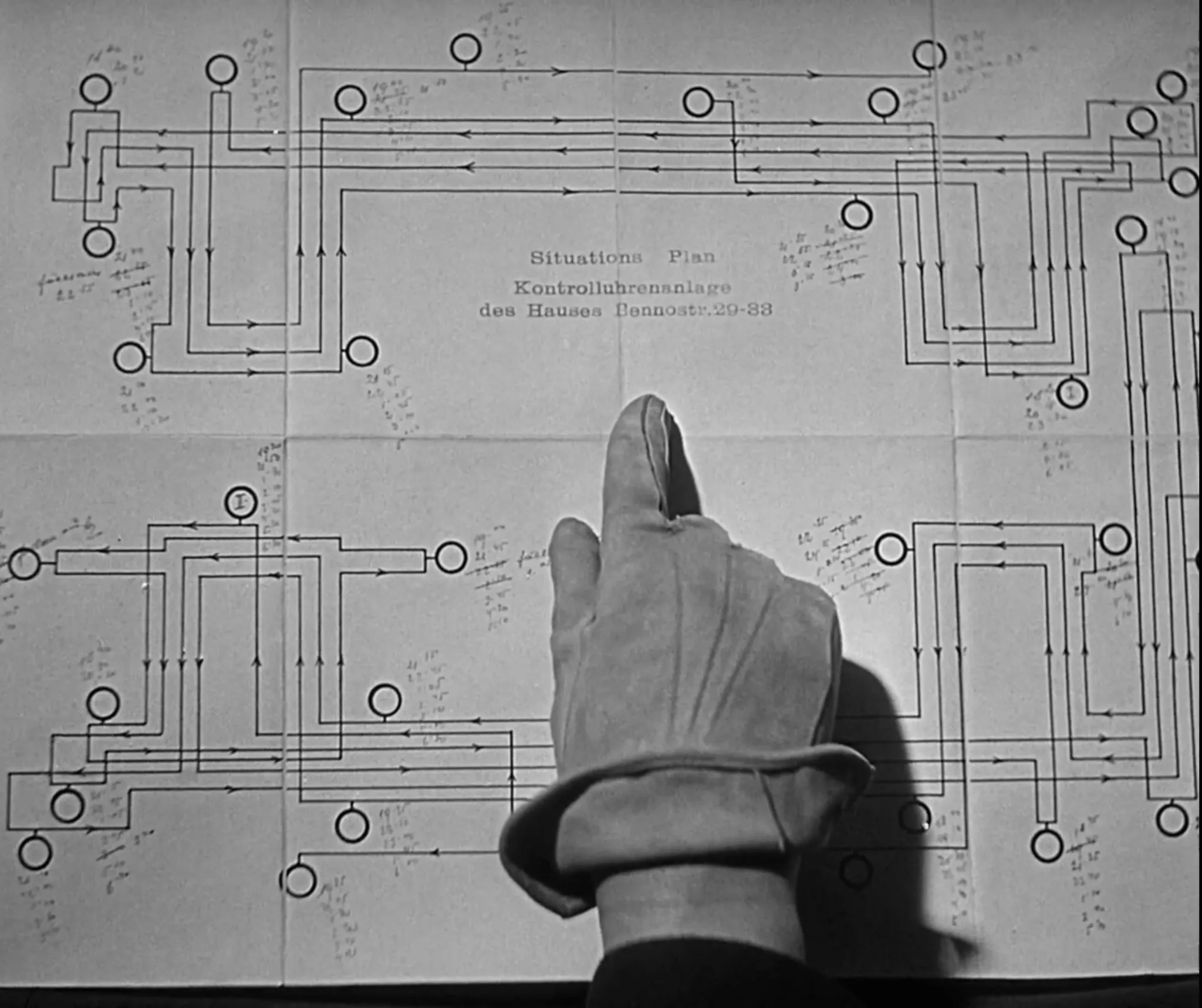

The police investigation montage introduces several visual motifs - variations on hands and mirrors, Hans Becket (Peter Lorre) grabbing his face, and maps - that will recur throughout the film. Variations also occur in the sequence below, in which Lang cross-cuts between the police, the criminal underworld, and the space occupied by the poor and the destitute, demonstrating the many ways in which these different social domains intersect and deepening the poetic force of the map motif.

Themes, Variations, and Reversals

Different motifs introduced earlier in the film - including the sounds of car horns and the whistling of "In the Hall of the Mountain King" and the visual appearance of mirror reflections and hands - are reintroduced in each of these sequences. In the extended chase and the underground trial sequence, Lang uses variations of these same elements to audaciously and forcefully upend the viewer's moral self-righteousness, engendering human sympathy for a child murderer without downplaying the vileness of his actions.

All of these different audio, visual, and moral dynamics come together in the film's concluding gesture, as a policeman puts his hand on Beckert and says, "In the name of the law."