Please update your browser

Your current browser version is outdated. We recommend updating to the latest version for an improved and secure browsing experience.

Battleship Potemkin

- Sergei Eisenstein

- USSR

- Montage

- Silent Film

- Edmund Meisel

- Sergei Eisenstein

- Grigori Aleksandrov

- Jacob Bliokh

- Eduard Tisse

Many of the writers who celebrated the artistic resources of the fledgling cinema in the first decades of the twentieth century stressed its unique capacity to depict continual metamorphosis in both space and time. The main alternative was to stress the constructive possibilities of the interrelationship of different visual ideas through editing.

The foremost proponent of this approach, Sergei Eisenstein (1898-1948), argued that through montage, cinema was able to mobilize the juxtaposition of fragments held in dialectical tension with one another to create new forms of artistic unity, what he called (in "Dickens, Griffith, and the Film Today") “an organic embodiment of a single idea conception, embracing all elements, parts, details of the film-work.” [1]

Eisenstein's Montage

Battleship Potemkin (1925) was made and released to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of a failed 1905 political uprising that was seen to anticipate the success of the later Russian Revolution that began in 1917. The mid-1920s period in which the film was made was marked by great excitement about the seemingly limitless possibilities of the new medium, which was given pride of place in Soviet culture. Lenin had viewed cinema as the art best equipped to reach the masses and therefore the most important art, so he gave license to filmmakers like Eisenstein to actively experiment with cinematic form and structure as well as the nature of perception.

Eisenstein described montage as a Hegelian process in which a shot meetings its opposite (in terms of orientation, shot scale, composition, structure, and intellectual content) would then be brought into a dynamic synthesis. In the year surrounding the creation of Battleship Potemkin, he frequently invoked the idea of the "Kino-Fist" to describe his explosive conception of how these sensory shocks would affect viewers (best exemplified by the shameless use of a careening baby carriage in the Odessa Steps sequence below).

These relations are predicated upon a broader understanding of the psychology of film viewing that derived from the much-discussed experiments of Lev Kuleshov (1899-1970). Kuleshov had taken the same brief shot of the face of pre-Revolutionary movie star Ivan Mosjoukine and juxtaposed it with a bowl of soup, a dead child, and a reclining woman. Viewers are said to have interpreted this same image of an enigmatic face differently depending on which of the other shots was juxtaposed (reading it as expressing hunger, sorrow, or enticement). With these ideas in mind, Eisenstein conceived of montage as a reflexive reworking of principles fundamental to the sequential structure of cinema.

Images of Prometheus

The young Karl Marx (1818-1883) described Prometheus as "the most eminent saint and martyr of the philosophical calendar" in his doctoral dissertation of 1841. He was building upon a tradition epitomized by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). Goethe reinvented and reinvigorated the myth of Prometheus in his eponymous 1774 poem, transforming him from a figure rightly punished for his transgressions into an emblem of the creative imagination:

Here I sit, forming men

In my image,

A race to resemble me:

To suffer, to weep,

To enjoy, to be glad -

And never to heed you,

Like me!

Lord Byron's 1816 "Prometheus" treats its subject as the embodiment of Romantic ideals, "[strengthening] Man with his own mind." Byron claimed to have been so enamored of the Prometheus myth that he could “easily conceive its influence over all or anything that I have written” and associated the figure with the nineteenth century's most ambitious and ambivalent figure in his 1814 poem “Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte,” where he yearns for the exiled ruler to “share with [Prometheus], the unforgiven, his vulture and his rock!… [and] in his fall [preserve] his pride.

In "History," an essay written the same year as Marx's dissertation (1841), the American Ralph Waldo Emerson (1883-1882) re-interpreted this Romantic Prometheus as a symbol of intellectual independence and self-actualization:

The beautiful fables of the Greeks, being proper creations of the imagination and not of the fancy, are universal verities. What a range of meanings and what perpetual pertinence has the story of Prometheus! … Prometheus is the Jesus of the old mythology. He is the friend of man; stands between the unjust “justice” of the Eternal Father and the race of mortals, and readily suffers all things on their account. But where it departs from the Calvinistic Christianity and exhibits him as the defier of Jove, it represents a state of mind which readily appears wherever the doctrine of Theism is taught in a crude, objective form, and which seeks the self-defence of man against this untruth, namely a discontent with the believed fact that a God exists, and a feeling that the obligation of reverence is onerous. It would steal if it could the fire of the Creator, and live apart from him and independent of him. The Prometheus Vinctus is the romance of skepticism.

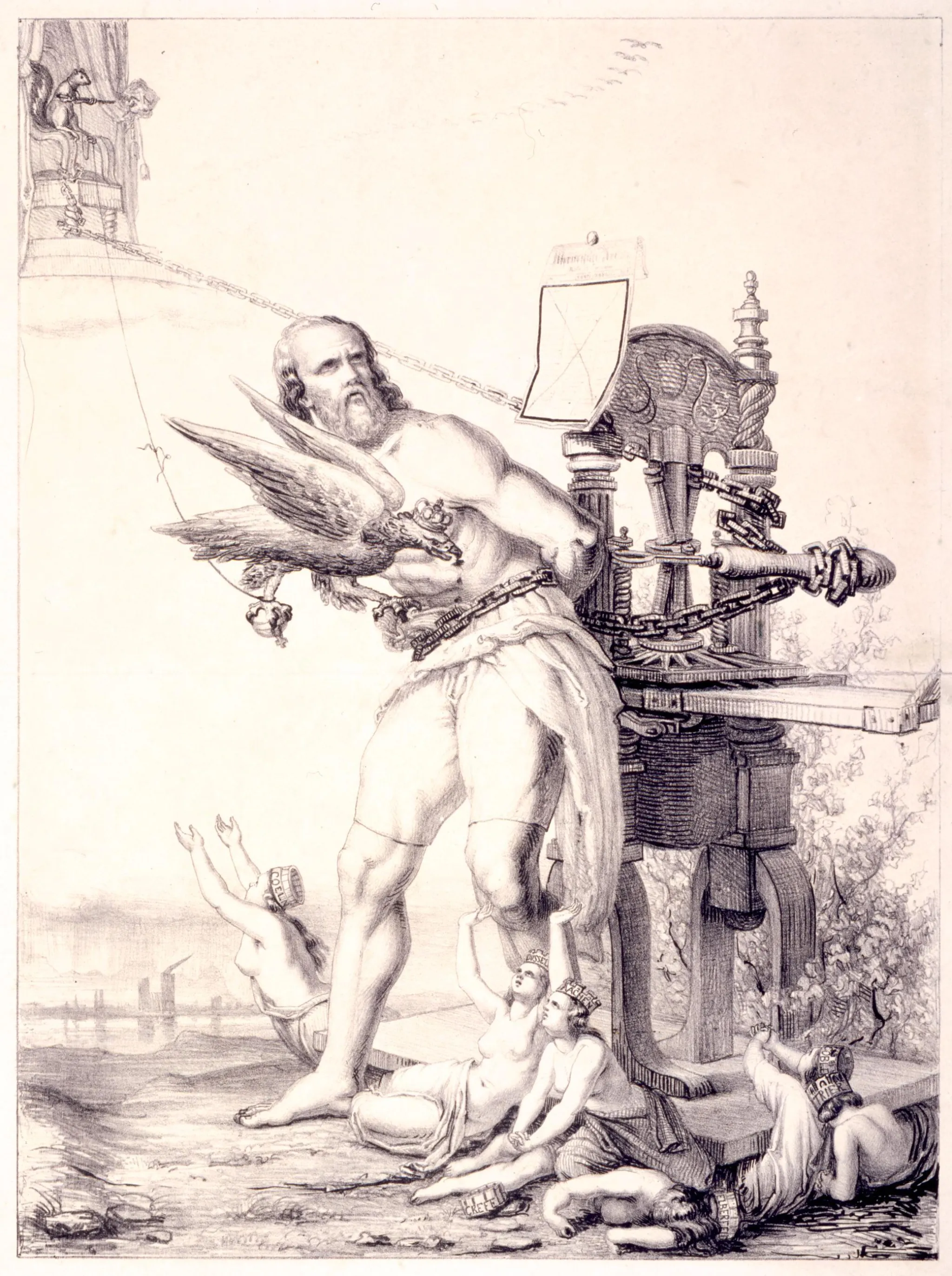

Promethean allusions abound in Marx's writings, and he characteristically described the accumulation of wealth as "[riveting] the labourer to capital more firmly than the wedges of Vulcan did Prometheus to the rock” in Das Kapital (1867-1894). Appropriately, the most important left-leaning independent production/distribution company in late Weimar Germany – active from 1926 to 1931 – was called Prometheus Films.

These different ideas and images of Prometheus continued to circulate actively into the 20th century and the figure of Prometheus became an ideological battleground in the 1920s and 1930s, interpreted as an avatar of struggling workers in a 1930 mural by Mexican painter José Clement Orozco, as embodying the spirit of capitalism in Paul Manship's gilded Rockefeller Center statue (1934), and as an archetype of Nazi strength by Arno Breker (1934).

The Lion Rises

Much as Marx had reworked the image of the Romantic Prometheus, Eisenstein attempted to address the present by revitalizing rather than disavowing earlier traditions.

In the final thirty seconds of the Odessa Steps sequence, he offers a brazenly pedagogical demonstration of the potential of montage. After the battleship fires at the Odessa theater, Eisenstein links three clusters of three discrete shots, creating an impression of rounded motion by juxtaposing angles in a musical fashion – first, right, center, and left with the putti; then, left, right, and left with the explosions; and finally, right, left, and further left with the lions. This is followed with a musical variation of four explosions that recapitulates the patterns in the previous three clusters.

Each of these clusters is spatially disconnected, but they are connected through rhythmic, morphological, and symbolic associations. There is no motion of any kind within or between any of the shots of the statues in the first or third cluster. That the sequence nevertheless gives the impression that the lion finally rises up at the end testifies to the continued relevance of cinema’s nineteenth century roots in persistence of vision and optical illusion. It also reflexively demonstrates the cinema’s revelatory potential; the creation of a montage synthesis in the mind of the viewer enables one to “see” perceptual and conceptual relationships that would otherwise remain invisible.

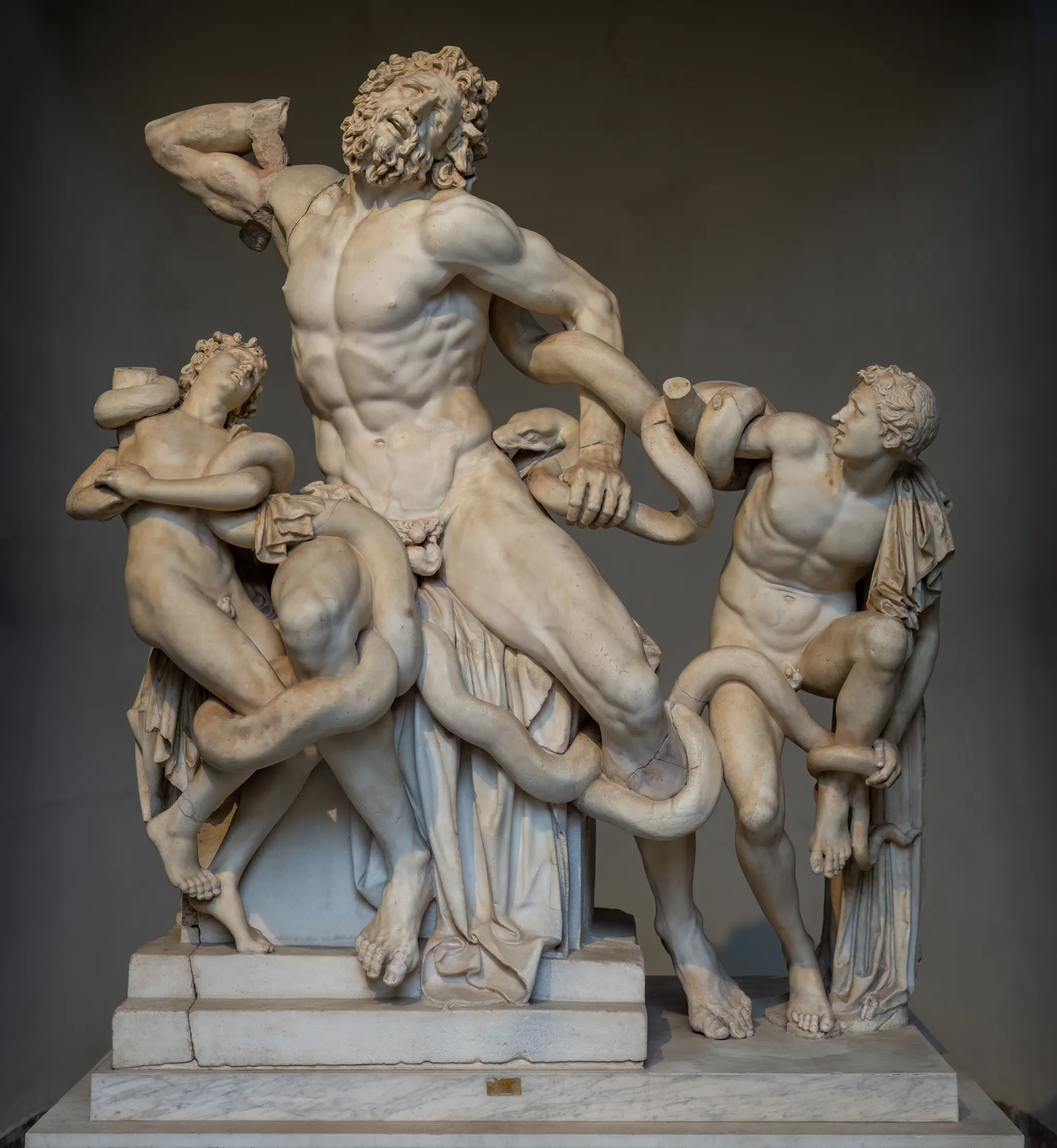

It is surely also significant that the still images that are the constitutive essence of film are metaphorically linked in the sequence from Battleship Potemkin to statuary. In a late essay on El Greco (1541-1614), Eisenstein singled out his painting of The Laocoön (1610-1614) as one of the works in which the elongated bodies and torqued planes characteristic of the painter’s mature work “explode” out of the frame and become genuinely “ecstatic” [2]. This painting is itself a reworking of the most famous of all Hellenistic sculptures, with the emphasis shifted from the horizontal to the vertical.

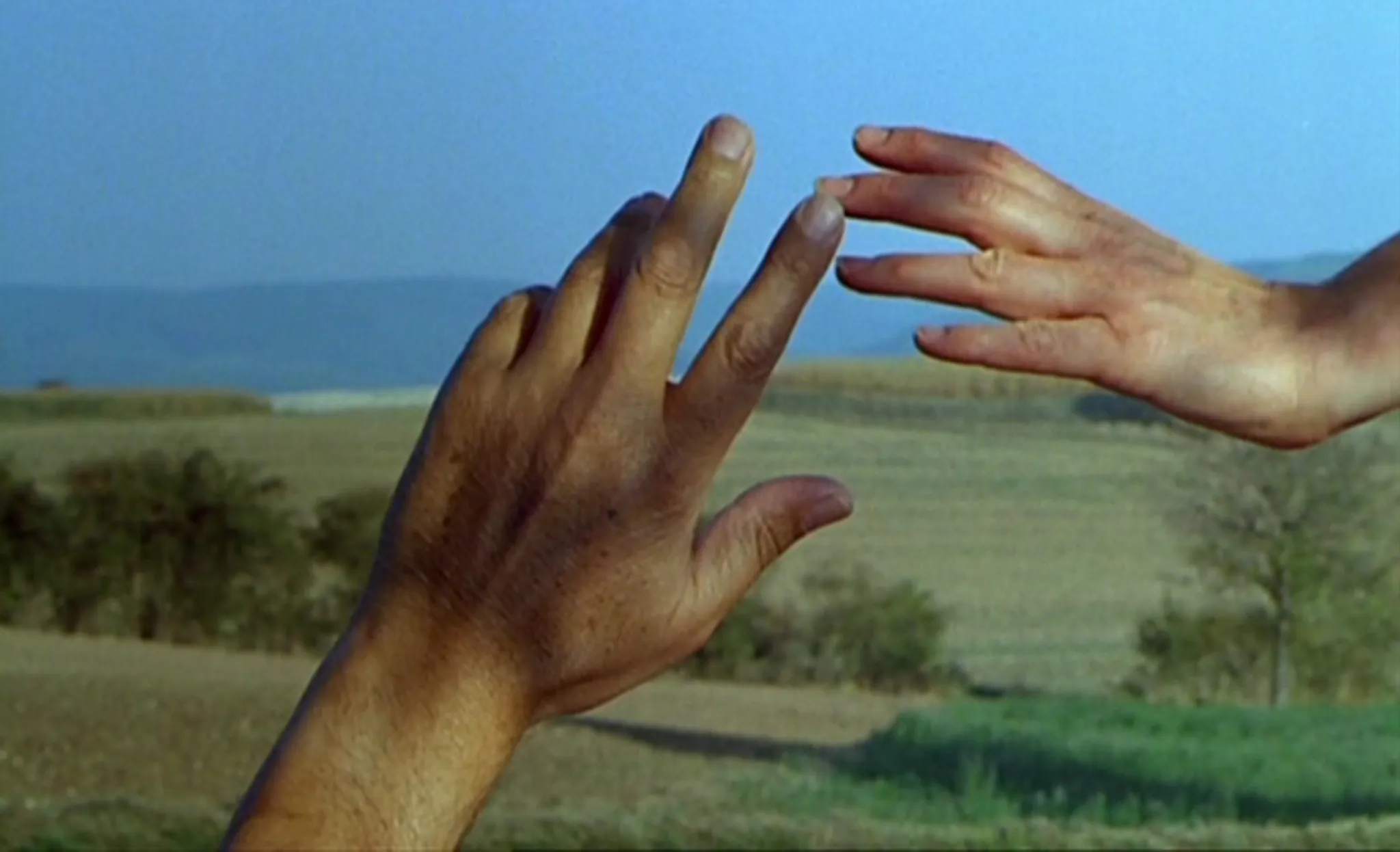

It is in fact only through montage, with the formation of a synthetic “image” across space and in time, that sculpture becomes a truly salient reference point for cinema. As Jean-Luc Godard, the most important montage filmmaker of the second half of the twentieth century and a filmmaker greatly concerned with tactile metaphors and the presence of hands once put it: “In montage… one has a moment physically, like an object.”

What might it look like to “have a moment physically” as an object? Perhaps it would look something like Auguste Rodin’s The Hand of God (1895-1907), in which figures appear to be extracting themselves from a divine hand modeled on the artist’s own. Rodin reflexively fuses depictions of physical and mental creativity, activating all dimensions of space and evoking what the poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) characterized as a “magical in-between” state, a metaphysical refusal of emptiness.

This image perfectly encapsulates the many Promethean aspects of Eisenstein's conception of montage.